It was Richard Fortey, of Natural History Museum fame, who described the underlying the geology as the ‘Collective Unconsciousness’ that moves and binds us surface dwellers. We are in thrall to the underlying rocks – whether it is radon escaping from a Devonian granite, an earthquake wreaking destruction in Turkey, or a volcano erupting in Indonesia. To not be paying attention the rocks and geological processes beneath our feet is to be not paying attention to half the story.

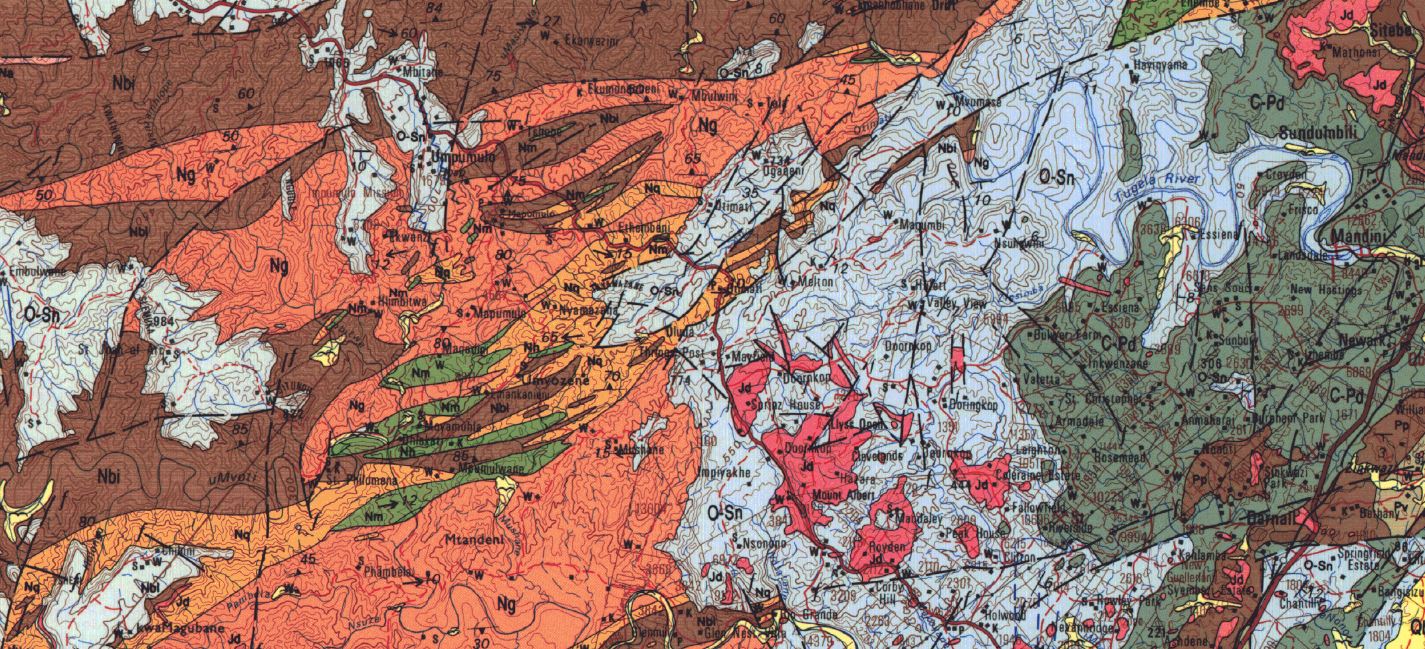

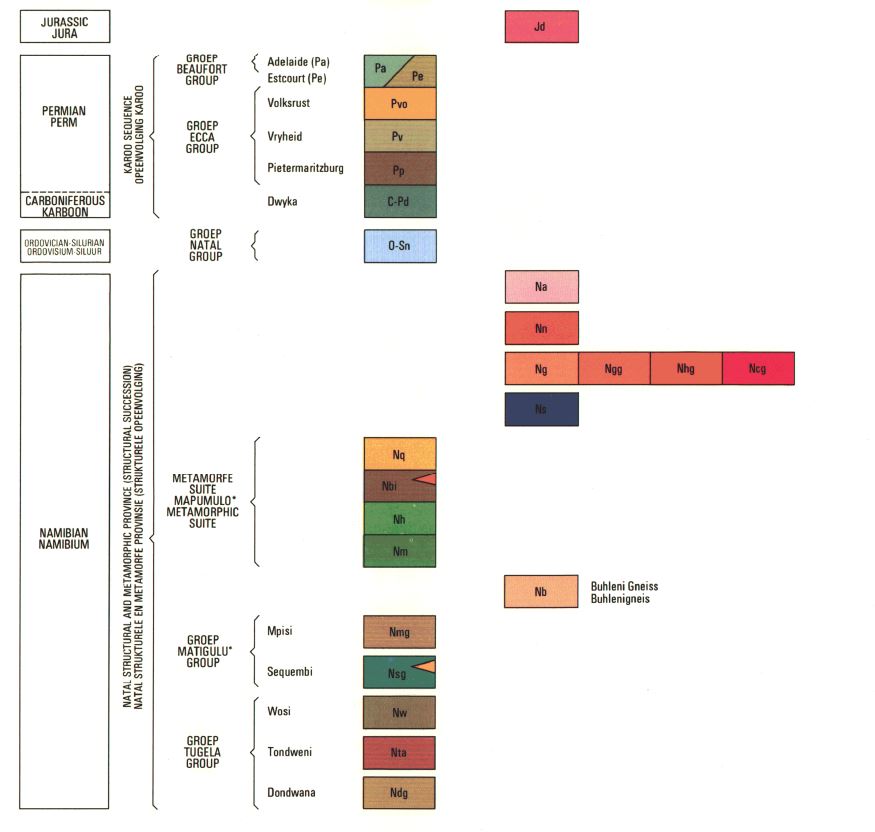

I remember when I first saw a geological map. It would have been in my first-year geology, and the map would have been that of the geology of the entire country. It was kind of familiar – certainly the geographical boundaries were well known, as well as the location of the major cities. But the rest was new – splashes of colour in wonderfully arrayed splashes of colour, with a geological column to the right, and a key providing a brief geological description of the various rock types. It was an adventure in time travel, if you can just get your head into the right space. Those coloured blocks at the base of the geological column hinted at times more distant than I could imagine. The legend said Precambrian. Which meant that those rocks were all older than 541 million years. In fact, most of them were older than a billion years. It boggled my mind.

A sweep of geological time extending back 3.5 billion years

Then there were other coloured blocks higher up in the column – blue denoting Ordovician and Silurian sandstones, a greyish green, Carboniferous and Permian glacial deposits, random dashes of red, Jurassic aged dolerite. The beautiful arrangement of colours on the map showed the lateral distribution of the various formations that made up the geological record – a sweep of time from 3.5 billion years ago to loose, wind-blown sediments barely 10 000 years old, if you didn’t count the modern-day alluvium in the river valleys.

The geological column provided the absolute ages of their deposition thanks to the hard work of the geologists and the physicists who had dated them in the laboratory. But that wasn’t all – that map showed the faults, it showed the folds, it showed mineralisation, the functioning mines, and the closed ones too.

A geological column

The most important tool is a cheerful demeanour

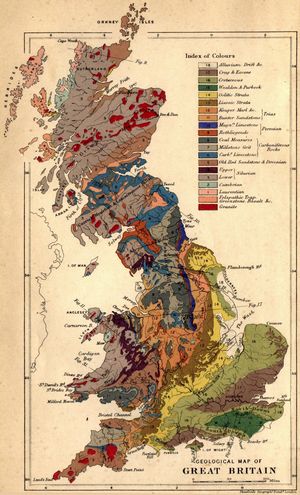

It was a wonderful thing. And thinking about it a little more, it was quite staggering, for the entire country had been mapped, and mapped in detail, by geologists who went out in the old days in ox wagons, on horseback, on bicycles, carrying a compass, a hammer and a topographical map if they were lucky. Nowadays they have 4x4 vehicles, GPS, GIS and satellite imagery. Google Earth is available to everyone. The most important tools are a cheerful demeanour and a thirst for adventure. Walking all day in the hot sun or tipping rain takes a special kind of person. Then there are snakes, scorpions, flash floods, thorn trees, lions, wolves, grizzly bears, nettles or whatever nasty you can think of , trying to take the jaunty grin of the geologist’s face.

It is detective work of the highest order

Every contact between the different rock formations has to be walked out and plotted onto the base map. Every formation has had to be described, sketched, sampled and photographed. And once the various formations have been mapped out, an attempt has to be made to explain the geological history of the area being mapped. It is detective work of the highest order – and it can be addictive.

Why don’t they seem to feature?

With so much effort having been put into the making of geological maps, I have to question why they don’t seem to feature that prominently in the geography class? From a geological point of view, I would never venture out into an unknown area to carry out any fieldwork without first consulting the geological map – provided that there is one available of course.

A geological lineament

If were to study drainage basins, or the slope morphology, or the distribution of vegetation, I would go to the geological map first. Rivers will exploit weaknesses in the rock – weaknesses that may simply be the difference in hardness between a sandstone and a mudstone. Or the weakness provided by a fault line where the rock has been broken up or ‘brecciated’ by the rocks have ground past each other along the fault plane. Or the granite batholith that underlies the landscape and leads to radial drainage. Or the folded sediments – anticlines and synclines – that alternately expose hard and soft sediments along the course of the river.

Studying slope morphology and labelling the various components of a slope is all very well if the underlying rocks are uniform, but this is rarely so, and a hard capping of quartzite or dolerite is going to control the shape of the slope. As are the folded sediments in a tectonic collision zone. As is a granite batholith poking its bald head above a windswept heath.

The geology is in control

It was Richard Fortey, of Natural History Museum fame, who described the underlying the geology as the ‘Collective Unconsciousness’ that moves and binds us surface dwellers. We are in thrall to the underlying rocks – whether it is radon escaping from a Devonian granite, an earthquake wreaking destruction in Turkey, or a volcano erupting in Indonesia. To not be paying attention the rocks and geological processes beneath our feet is to be not paying attention to half the story. The geology is in control.

The World's First Geological Map.

I think I have made my point. Reach out to your local Geological Survey and buy the local geological map. Most maps also come with an explanatory book, so that is also worth the money. Perhaps a local geologist can be persuaded to hang out with you and your class – she may even bring some rocks typical of the region along. It will be a wonderful time for all. .

An Invitation

Start your geographical adventures by reading our articles here. They are pertinent to the physical geography courses that we have to teach, and do much to frame the subject and to provide insights that are not normally to be found in the text books. Enjoy, and leave your comments and requests in the comments section.

Hang out with fellow geographers here, check out what is happening here, and go see some amazing videos of wonderful landscapes here. And last but not least, find amazingly interesting snippets which bring earth sciences and geography into our everyday lives here.

Want to come adventuring? Who wouldn't? So sign up for our newsletters and stay informed when we launch new courses or go off on happy wanderings.

A promise - no spam, no nonsense, no passing on of your details