The Deepest Descent

The bathyscaphe Trieste was launched one January morning into a stormy Pacific Ocean with one goal - to descend nearly eleven kilometres to the floor of the Marianas Trench - the deepest point on Earth. No one had ever been that deep before, and so it was two brave men who set out on that vertical journey from which there was a chance they would never return. Read on to find out more....

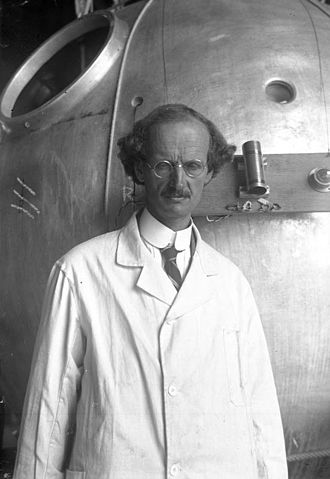

On the 23rd January 1960 a submarine – but more than that – a specially designed diving machine built for one thing only – to dive to the deepest places on earth – was put in the blue water of the Pacific. This wasn’t any place in the Pacific mind you, but a position first discovered by HMS Challenger back in 1875, when they sounded a depth of 8184 metres. At the time of that first Challenger Expedition, little did they realise that they had just sounded the deepest point on earth. The Challenger Deep, as it is now known, was about to be challenged again, but this time by the bathyscaphe Trieste. It had been built by Auguste Piccard, a Swiss balloonist, explorer and physicist who had for years been carrying out pioneering work on climatology and the composition of the high atmosphere. A visit to the 1933 World Exposition in Chicago, where he saw the work of Otis Barton and William Beebe, made him change course, directing his high-altitude ballooning skills to that of developing deep sea diving bells, or bathyscaphes.

Operations in Italy, and then with French Navy and finally the US Navy, who had bought his submarine, the Trieste, in 1958, lead to Project Nekton to the Challenger Deep.

Which brings us back to the launch of the Trieste on that day in the middle of the ocean. They nearly called it off, for the seas were rough and the sharks were circling. After long debates in the wee hours of the morning, and thumbs ups from some members of the team, Lieutenant Don Walsh and Jacques Piccard were delivered to the Trieste, the hatches were battened down and the descent commenced.

Trieste in her element

The Challenger Deep is the deepest known point in the ocean. It lies approximately 350 miles southeast of Guam, and reaches a depth of 10 929 metres. That is just short of 11 kilometres. When you think that 1 cubic metre of seawater weighs approximately 1000 kg and there are 11 km of water above the floor of the trench, those pressures are huge.

It is so deep because it is the boundary between the Pacific Plate and the Filipino Plate

The trench is so deep, that if we were to drop Mount Everest into it, we would still have over 2 km of seawater between the ocean’s surface and the summit of the mountain. It is so deep because it is the boundary between the Pacific Plate and the Filipino Plate – a destructive plate boundary in fact – where oceanic crust is subducted below that of the adjacent plate. This tectonic activity has led not only to the ongoing destruction of the Pacific Plate, but the formation of the Marianas Island Arc, which includes the island of Guam and the Northern Marianas Islands. Ocean trenches are to be found on many of Earth’s plate boundaries.

Alfred Wegener came up with a mad notion of ‘continental drift’

When HMS Challenger was sounding the trench back in 1875, little did they realise what the significance of their discovery meant in terms of our understanding of the intricate mechanism that makes Earth work. It took a meteorologist called Alfred Wegener to come up with a mad notion of ‘continental drift’ which drove earth scientists to reconsider their view of the world. Perhaps appropriate, bearing in mind that August Piccard also started out exploring the upper atmosphere. HMS Challenger’s crew would never have thought that someday, 85 years later, a submarine would attempt to reach the bottom of that trench.

They would have turned instantaneously into pink pulp

And so, Trieste began her descent on that warm, rough Pacific morning. It must have been a sobering thought when they shut that hatch – there were no guarantees that they were ever going to make it back alive. If the pressures had overcome the strength of that steel ball in which they were sealed, they would have turned instantaneously into pink pulp which is not a very pleasant prospect. At a depth of 9000 metres a sharp bang shook the ship, and a crack in the plexiglass window was observed, but with all the instruments reading normal they continued with the dive, reaching the floor 4 hours and 47 after leaving the surface.

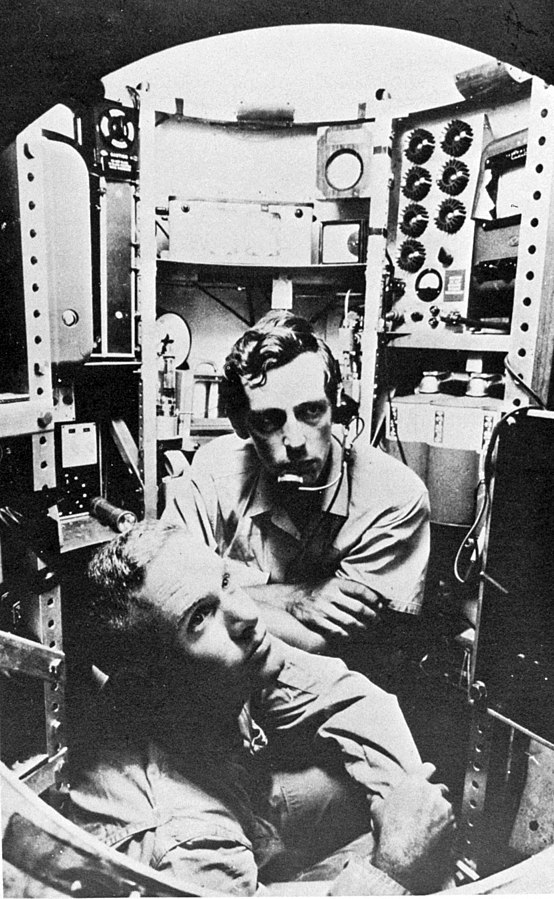

Walsh (left) and Piccard (right) in the bathyscaphe

They looked out onto a dark, hostile world and reported seeing flounders and soles, although their knowledge of these things was limited, and these observations have since been disputed. The ocean temperatures at these depths are in the order of 4 degrees Celsius and the inside of the bathyscaphe was not much warmer.

A tiny steel ball descending to perhaps the remotest place on Earth

Chocolate bars kept Piccard and Walsh fed, and possibly distracted as they made their historic dive and ascent. I guess you need calories too to keep out that bone-chilling cold. It took 3 hours and 15 minutes to get back to the surface – all told 8 hours and 2 minutes in a tiny steel ball descending to perhaps the remotest place on Earth.

Fear, cold and claustrophobia all had to be overcome on that epic descent – I guess having worked in and around the Trieste for years had given Piccard plenty of practice of being in cold, dark, cramped spaces and Lieutenant Walsh was a submariner by profession so he was also used to that kind of thing.

Old man Auguste Piccard must have been delighted

But that aside, these two men were heroes – supported by an amazing team, some from the US Navy and some from the original Italian team who built the submersible – and of course old man Auguste Piccard who must have been delighted to see his ship descend to the bottom of the ocean. Auguste Piccard died two years later.

August Piccard

Truly a tale of grand adventure, to a remote and hostile place on Earth, a place that exists thanks to the exquisite clockwork that makes our planet tick – Plate Tectonics.

We are putting a course on Plate Tectonics, the rock cycle, weathering and geology, so if you would like to be kept informed when we launch the course, please leave your name and best email in the box below.

If this resonates with you and you think it may be valuable to others, please share.

So looking forward to exploring with you